Livorno

Jewish life in Livorno was greatly favoured by political and economical measures, taken from 1548 to 1590, that granted foreigners freedom to practice religion, and commerce. The arrival in Italy, as well as on the shores of the Mediterranean in the East and North Africa, of the mass of Jews that had left the Iberian peninsula after the edict of 1492 and the forced conversions in Portugal, signified a dramatic change in diasporic Jewry. Traditional local communities (for example the italkim in Italy and romanioti in the territories of the former Byzantine Empire) found themselves confronted by a Jewish natione not only different in traditions, but also bearer of social and cultural traits that favoured it over other communities – in particular a wider familiarity with languages and international relationships, features that would prove decisive in the commercial field. So it was not without a specific interest if Cosimo I, Duke of Florence since little more than a decade, sent a specific invitation in 1548 to Sephardic Jews, granting protection from the Inquisition to those who would settle in Livorno.

To Cosimo I, as well as to any other European ruler of Early Modern times, Jews (and especially those fleeing sefarad) must have appeared as an anomaly: a people without a land, divided in groups of very different dimension, often on the move, yet partaking of a common set of experiences, of a common language, Hebrew, that even where it was not currently spoken had a firm role not only in the liturgical field. An anomaly that could be organized into an opportunity for growth, as was eventually the case in Livorno.

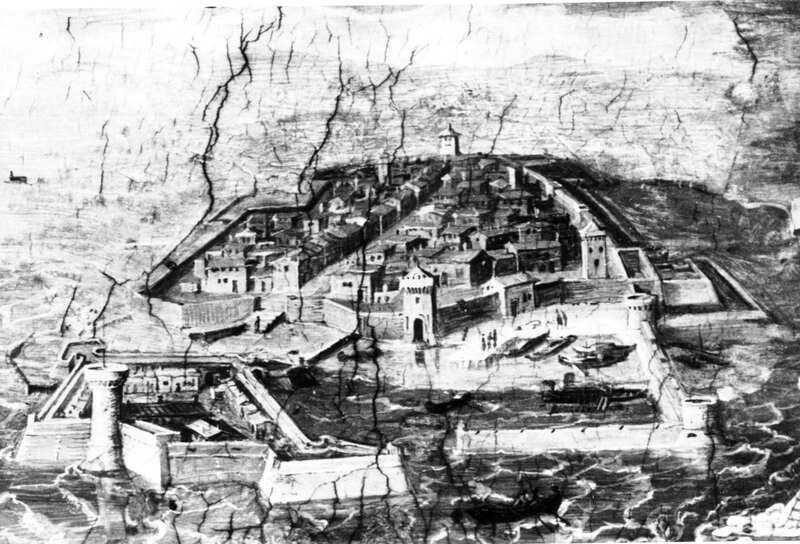

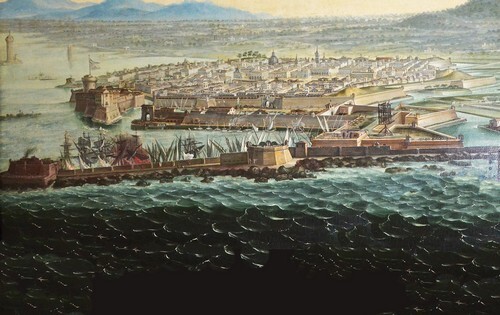

A new effort to open Livorno to international routes and commerce took place in 1586 when the invitation to settle and operate was extended to the English, themselves not only foreign but mostly adherent to the Anglican church, born of a schism from Rome not so distant in the past. Little time passed that the famous leggi livornine were passed, in 1591-93. Now special privileges in the religious field (more for the Jews, it must be said, than for the non-Catholic Christians) and in terms of customs taxation were extended to merchants of “any nation, Levantini, Ponentini, Spagnuoli, Grechi, Tedeschi, Italiani, Ebrei, Turchi, Mori, Armeni, Persiani...”.

The influx from Greece, Germany, England, Holland as well as of Jews of different origin made Livorno into an extraordinary living laboratory of cultural and human diversity, allowing the Grand Duchy of Tuscany to reach North Africa, the East Mediterranean and the seas of Northern Europe through a complex network of economical and mercantile relationships.